Ask microCOVID: Why doesn't a negative test mean someone is safe?

Ask microCOVID: Negative COVID Tests

We get a lot of questions about how to use COVID Test results. Some of these include:

If I get a negative test before I go home to see my parents, then I don’t have COVID, right?

My housemate wants to date someone who does risky behaviors, but gets tested every other week. Should we discount their behaviors because of the tests?

My church is planning to have large in person gatherings. They told everyone to get a rapid test within 3 days of the event. Does this seem crazy and/or dangerous to you? Or is it within the realm of possibility. ~S

Today I’m here to answer these questions using research, microCOVID, and some math.

Key Takeaways: If you’d rather be spared the math, the short answer is no, getting a one-off test (or even weekly tests) is not effective at preventing COVID spread. Limiting your risk and quarantining is the only foolproof way to ensure you don’t pass on COVID.

Testing isn’t useful on it’s own

Getting a negative PCR test* (while otherwise going about life as normal) tells us that a person is 25% less likely to have COVID today than we thought before. This is because the test doesn’t work for COVID contracted in the 4 days leading up to the test. Add that to the delay in getting the test back, and there are now 6 days of potentially risky behavior in which the person could have gotten COVID that the test wouldn’t show.

How should we interpret that? It probably shouldn’t change our behavior much. If you thought there was a 50% chance of rain today, you’d probably take an umbrella. If the weather report just as you left the door downgraded this to 37%, you’d still want to take that umbrella.

Getting a test every week doesn’t help this; you never know whether you are infectious until it is too late.

*assuming a 2 day turnaround time for the test. Beyond 4 days the negative test is essentially meaningless.

Rapid Tests are slightly better

Getting a negative rapid test back the same day they took tells us that a person is about 50% less likely to have COVID today than we thought before. Going by our weather analogy, that’s a 25% chance of rain instead of 50%. Maybe you’re willing to risk it, but I’d still bring an umbrella.

Like the PCR test, the usefulness of the rapid test drops rapidly after the test - after 2 days it is 25% effective, and after 4 days it doesn’t tell you anything.

Testing with Quarantining IS Effective

Since the biggest problem with tests is that they don’t tell you if you got exposed to COVID starting 4 days before the test, the easiest way around this is to not expose yourself to any risk starting 5 days before the test.

If someone quarantines for 10 days and take a test on day 6, then the test is 75% effective! On top of that, completing the 10 day quarantine without symptoms reduces the likelihood they have COVID by 95%. These effects stack and together are 99% effective. That 50% chance of rain is now 0.5%. Go ahead and go outside without an umbrella.

Caveat - Sometimes 99% isn’t good enough

Getting rained on isn’t so bad; I’ll be a little cold but I’ll dry off. COVID is significantly worse - between the risk of death, long term heart damage, long term neurological effects, and risk of giving any of those to someone I love, it’s not a good time. So 0.5% for a single event is still too high for my tolerances.

Fortunately most people don’t start out with a 50% chance of having COVID. A lot of parts of the United States and Europe have 1-2% of the population infected. Reducing this by 99% via quarantine + test yields a 0.001% chance of being infected, which is something I can live with.

However! If a person has done something riskier, like come into contact with someone who tested positive for COVID, gone to a crowded bar, or is showing symptoms, their risk could be high enough that I want better than a 99% reduction in the chance they have COVID. In this case, a 14 day quarantine with a test on day 6 should suffice.

Conclusion

To sum up, simply having a negative test result tells us very little about a person’s risk. A negative test with a 10 day quarantine is sufficient to feel safe around most people. A negative test with a 14 day quarantine is necessary for someone who has had a known exposure to Covid-19 or is showing symptoms.

Nitty-Gritty: How we calculate Test Characteristics

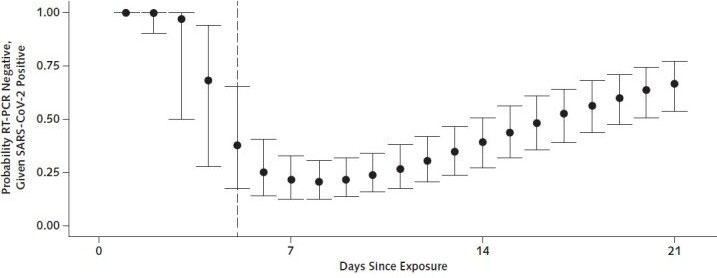

The current PCR COVID tests (the ones where someone sticks a Q-tip in your nose) are reported as having a best-case false negative rate of 20%. On top of that, the false negative rate increases as you get away from the optimal day:

Here’s the average false negative rates in chart form:

| Days since infection | False Negative Rate |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1.0 |

| 2 | 1.0 |

| 3 | 0.95 |

| 4 | 0.65 |

| 5 | 0.35 |

| 6 | 0.25 |

| 7 | 0.2 |

| 8 | 0.2 |

| 9 | 0.2 |

| 10 | 0.25 |

One-off tests

If you did something risky N days before taking a test that came back negative, you can look up the chances that the test will catch that. Multiply the microCOVIDs from the event by the False Negative Rate for that day and you get a revised microCOVID risk*.

*Note - this is accurate for risks of ~100,000 microCOVID and below. If a person is carrying a higher risk, you may need to use Bayes Theorem for accuracy.

Example 1 - optimal test You took a masked outdoor walk with someone who tested positive for COVID a few days later (800 microCOVID). You got a test on day 7, and it came back negative. Your new risk is 800 * 0.2 = 160microCOVID.

Example 2 - mistimed test You did the same walk, but got tested the 4 days later. The false negative rate is 0.65, so your risk is 800 * 0.65 = 520 microCOVID.

Example 3 - test + quarantine You did the same walk 10 days ago. You took a test on day 7 and it came back negative. You have not developed any symptoms. 95% of people who develop symptoms do so within 10 days. Since you haven’t developed symptoms, your new risk is 800 * 0.2 * 0.05 = 8.

Quarantining alone would have brought your risk to 800 * 0.05 = 40.

As you can see, quarantining is more effective than testing at reducing the risk you pose to others, but it can be used in conjunction to stack the effects.

Periodic Testing

So what if someone get tested every week? Let’s say they work outside the house in an office with masks and reduced capacity. You calculate their risk to be 100microCOVIDs a day.

(For ease of math, we’ll say that they work 7 days a week, but we hope this doesn’t describe anyone!)

| Sun | Mon | Tues | Wed | Thurs | Fri | Sat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dosage Test FNR Effective Risk |

100µC .25 25µC |

100µC .2 20µC |

100µC .2 20µC |

100µC .2 20µC |

100µC .25 25µC |

100µC .35 35µC |

100µC .65 65µC |

| Dosage Test FNR Effective Risk |

100µC .95 95µC |

100µC 1.0 100µC |

100µC 1.0 100µC |

100µC, Tested 1.0 100µC |

100µC - - |

100µC, Test Returned - |

In the above calendar, our hypothetical person got tested on the second Wednesday and got the test back negative on Friday

If we hang out with them on Friday, we sum up their risk from 2-9 days prior, or the first Thursday through the second Wednesday. Without the test, we would get 700microCOVID. With the test, we get 520microCOVID.

That’s only a 25% reduction. What happened? The fact that tests are very poor at detecting infections in the last 4 days, combined with a two day turnaround (which is, in our experience, the lower end), means that by the time we get a test back, only 2 days that matter are really tested for.

If you want to play games with your risk to get the most out of the test, you could see them on Monday (two days before they take the test) and record 700microCOVIDs. If their test comes back negative, you’d go back and adjust your risk based on that to Sunday-Saturday, which gives 210microCOVID. Of course, you won’t know that until Friday, so you’ll need to avoid anyone on a risk budget below your new risk level until then.

What if you get tested more often? You’d be more likely to catch an infection if you got it, but you would never be able to use testing to reduce your current-day risk level below 520 (assuming a 2 day turnaround). Based on these false negative rates, if you wanted to be maximally likely to spot an infection via testing, you’d want to get tested about every 5 days, so that the next test would cover the blind spots of the previous one.

Rapid Tests

Here is how I adapted this data for rapid tests:

- These tests appear to have similar performance to PCR tests (20% false negative).

- We are assuming they follow a similar false negative schedule.

- The main advantage is getting the test back and then immediately going to an event - in the above scenario, seeing the example person on Wednesday knowing they already got a negative test would yield 360microCOVID, or about half the risk without the test.

- The very next day, that goes up to 440, so the window of usefulness is short.

FAQ

Does getting a negative test mean a person wasn’t infectious at the time of the test? If someone tested negative the day I saw them, but tested positive a few days later, am I safe? We think there is strong evidence that discredits this. The primary reason for thinking this is not the case is that tests seem to be most effective after symptoms start, while Byambasuren et al found that infectiousness seems to peak 1-2 days before symptoms start, hence it would appear that most people are most infectious before tests turn up positive.

Shouldn't you be using Bayesian Statistics? Bayes' Theorem states that the reduction of risk that occurs from a negative test is slightly lower than what we stated above. However, the error introduced by the method we suggest above is small (1%) if the prior risk is below 10,000 microCOVIDs. It is relatively difficult to get more than 10,000 microCOVIDs without coming into contact with a known positive case. We will discuss how to handle this is another post.